This pieced skin cover is so primitive it looks like it came straight from the stoneage and wouldn’t look out of place in the cartoon “The Flintstones”. Vivid saturated natural Indigo and Orange-Red dyed strips, stitched together with coarse and shaggy natural shades of brown and black hide. Creating a tangible and expansive view into a long lost nomadic past.

These animal skin covers are rare, not much is known about their origins or use. James Blackmon had brought some of these to the marketplace in the mid nineties. Eventually an example from the collection of Dr John Sommer came back to the market via James and I snapped it up. Another example is held in the collections at the De Young Museum in San Francisco.

James Blackmon wrote, “ I would date the sheep skin rug to the late 19th or first part of the 20th because the dyes appear to be natural. It is difficult to date these things because there are not many examples to compare. I have seen pieces with only natural, un-dyed sheep skin used and I have seen one or two with some synthetic dyes used. This one I would say is in the oldest group of these skin rugs. I have had 5 old ones over the years and all came about 13 years ago. Since then I have not seen others of this natural dyed type. It must have been a small, remote community where these survived, since after they came to market and relatively high prices were established for them, none or only a very few have surfaced in the market place since. This defies the usual pattern and market logic for newly discovered, old ethnographic items. Once something is discovered there tends to be many more that come out of the woodwork to meet demand.”

Two examples were published in John Wertime's landmark article "Back to Basics: Primitive Pile Rugs of West and Central Asia" Hali 100 in 1998. Wertime discusses the use of the needle and it’s invention 20,000 or more years ago as being central to the original creation of these tanned covers. The ability to stitch animal skins together to make larger items probably pre dates woven rugs.

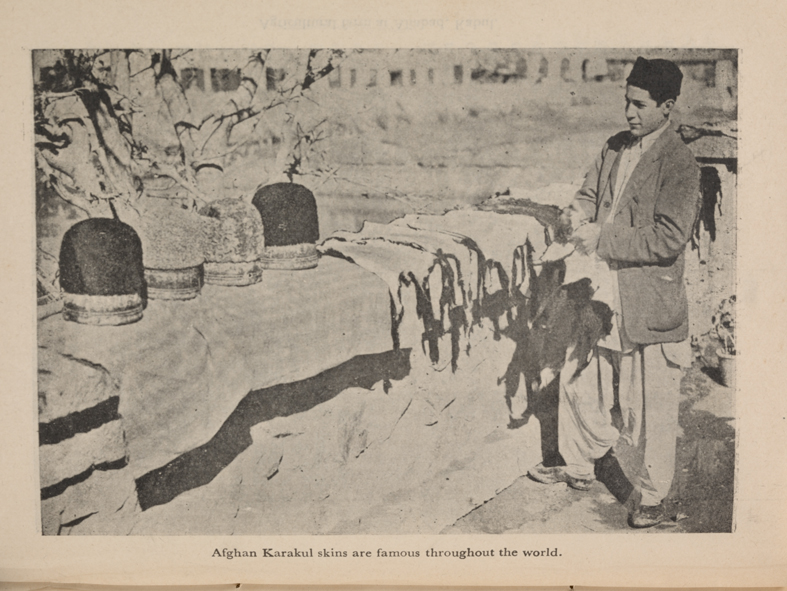

Made up of a number of pieces of animal hide strips in varying sizes, determined by the size and shape of the original hide. Stitched together to form a complete cover, usually from different types of animal. The preservation of the hides is a key element to their intended use. In Central Asia there is a long history of tanning. A distinction needs to be made between tanned goods where the fur has been stripped from the hide or alternatively softened and treated hides where the fur remains. Nazif Shaharani in “The Kirghiz and Wakhi of Afghanistan” discusses the method of treating Yak hide as well as Karakul Sheep, where the fur remains. “Yak hide is untanned but treated (oiled and softened).” Further, “The hides of sheep, goats, lambs, and kids are utilized in many ways. By treating and softening wool-covered sheepskin the Kirghiz make long fur overcoats. Sheepskins are also used to make fur mats that are used as mattresses.” In “Die Kirghisen des Afghanischen Pamirs” by Remy Dor & Clas Neumann some clues are given, “Next to the stove lay a sheepskin”. Included is a reference to an old Pamirs Kirghiz proverb. “In the past tanning was women’s work. So the following proverb attests: She who brings with her a skin of Russian leather, (supple and well tanned) will carry to wealth her marriage. Contrary, the property of a bad wife, she spoils the hide and puts the married couple in debt”.

The Wakhan corridor is extremely cold and inhospitable. The Kirghiz Yaks and Karakul sheep (turki qoey) have long thick coats as protection from the cold. Our rug illustrated here combines Karakul sheep and Yak or Goat hide. The Yak or Goat fur is particularly long, up to sixteen centimetres. Karakul sheep and Yak were the two types of hides that were “softened” for use by the Kirghiz. This process of softening hides, dip dyeing, stitching and embroidering produces a minimalist design aesthetic. Even though our example is primitive by nature it was created with a greater ideal that was of obvious importance to its original owner. At least 100 years old, this cover is remarkably well preserved. James Blackmon wrote, “All examples I’ve had show native patches and repairs and were in the early group. This one has less of this damage than the others. It was well kept.”

Dip dyeing was used as a technique to add colour and enhance design in some examples. Before sewing the strips of hide together, some covers were dip dyed. Dip dyeing is a process where the entire woven strip or selected piece of skin is dyed prior to stitching all elements together to complete the design. The obvious choice for dip dyeing would be white pelts, although I’ve seen black goat hair dyed with indigo! Arab Nomad Julkhirs from nearby Qataghan were also dip dyed. Minimalist design and sparing use of bold and graphic colour is evident in Kirghiz, Arab, and Uzbek weavings in the region. Indigo and deep saturated reds were commonly used throughout the Northern border regions of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.

Notes from a friend who has been conducting research in Afghanistan since 2007, his example has an embroidered edge and is not dip dyed. Mainly consisting of darker coloured strips of natural Karakul sheep.

Robert “News from my colleague in Kabul. He is a highly educated fellow from rural Wardak province South West of Kabul. I showed him my pieced skin rug, he recognised it instantly. According to him it is all sheep’s wool. He called it Pachmani. Pachm means wool in Persian. He said people do not create these pieces anymore but used to make them, even in his area which is Pashtun and where Pashtun Kuchi nomads used them. His grandfather has some at home. Interestingly he said that people never used these pieces as mats, they were far too costly for this purpose. Instead they used exclusively namads (felts) on the floor. The pieced skin covers were used as night covers or folded on the shoulders when seated in the tent during winter.

These pieced skin items are probably not some type of yatak or mat but rather covers. That’s why there is some embroidery on the part we considered as the back but which should be the front. To use fur in direct contact with the ground is not convenient at all, the fur can become dirty and damaged easily. Washing these pieced skin rugs would be almost impossible. It is very important to keep the tent clean and well ordered and the use of such materials is not really relevant in this case. It is better to use these covers close to the body for warmth. Contrary to this Namads (felts) provide a solution as a floor covering to keep the warmth in.

I remembered that a few years ago in Kirghizstan some nomads welcomed me in their yurt. They gave me a piece of camel fur as a cover for sleeping. I do not remember if it was a simple fur (I guess so) or a patchwork like ours but the practice is related. It is also interesting to note that Kirghiz use fur for some large warm jackets they call “Ton”.

I am not sure that the pieces discussed with my colleague were patchwork items with embroidered edging. They were probably simple furs un-dyed with simple patchwork strips.

A few years ago I found some fur pieces in the Peshawar market, they were simple, undyed and a little different. So they may be like those of the Pashtuns and our examples which are more elaborate, specifically pieces created by Wakhi or Kirghiz.”