Kochis and Nomad Primitive Rugs

Mohammed Ali described the life of Kochi nomads in Afghanistan in 1958. Ali mentioned that "The number of these tent-dwellers has greatly diminished during the past few years, and is still rapidly dwindling." Fifty years on and the Kochis of Afghanistan still roam freely. Another term Maldari is sometimes bundled in with Kochi or Kuchi . Maldari is primarily a term which describes those involved in animal husbandry and pastoralism, so can describe the way of life but not the people themselves. Maldari [maldary] Animal husbandry, pastoralism1 A large proportion of Kochi's are Pashtun sometimes referred to as Gipsy or Gipsy Pashtun.

Mohammed Ali described the life of Kochi nomads in Afghanistan in 1958. Ali mentioned that "The number of these tent-dwellers has greatly diminished during the past few years, and is still rapidly dwindling." Fifty years on and the Kochis of Afghanistan still roam freely. Another term Maldari is sometimes bundled in with Kochi or Kuchi . Maldari is primarily a term which describes those involved in animal husbandry and pastoralism, so can describe the way of life but not the people themselves. Maldari [maldary] Animal husbandry, pastoralism1 A large proportion of Kochi's are Pashtun sometimes referred to as Gipsy or Gipsy Pashtun.

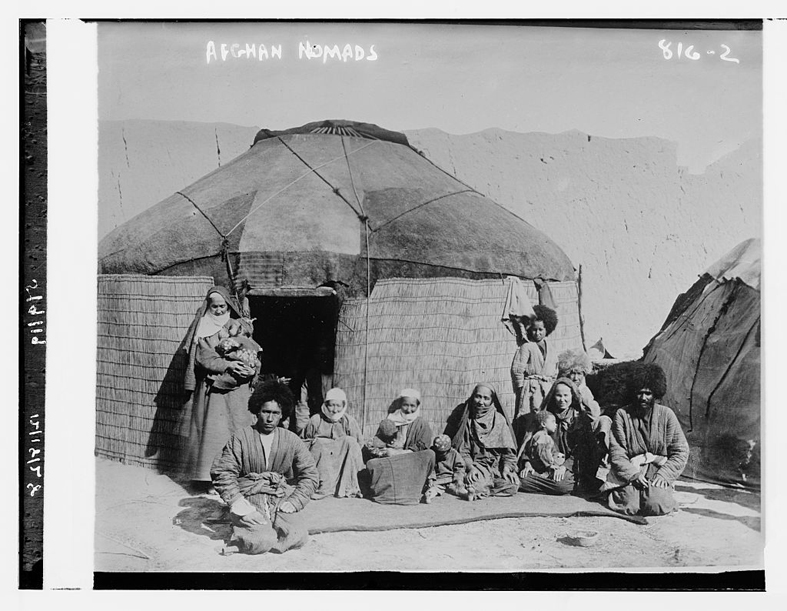

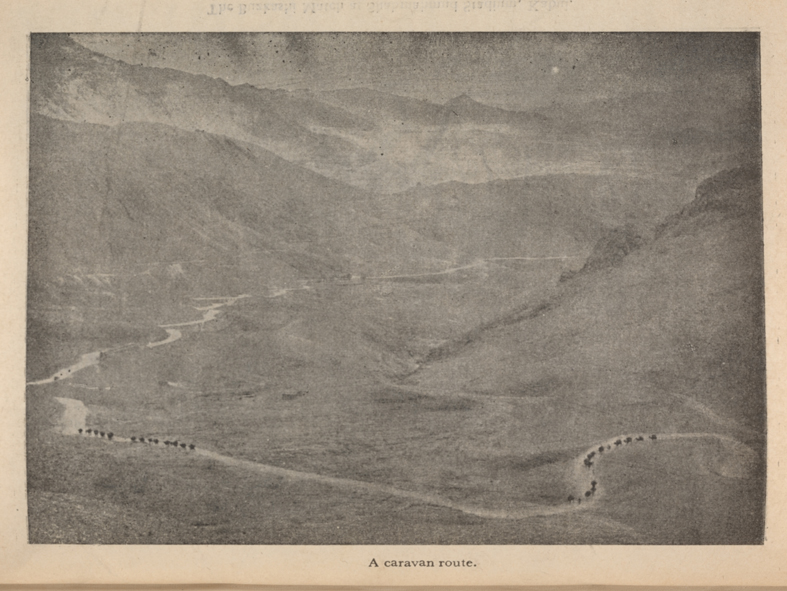

"A small portion of the population is still leading a sort of nomadic life. The Kochis (as they are called) have no fixed habitat and chiefly live in tents-Ghizhdi. These tents are made of extended lattice work, covered with black felt manufactured from wool, and can be easily taken down, folded up and carried on the backs of the camels, horses, cattle, sheep, goats. The flocks and herds are driven back and forth between the lowland and highland pastures, over routes which they and their ancestors have followed for centuries. In so doing they generally cross international boundary lines, but it is often without objection on the part of the governments concerned. They claim certain grazing rights in pastures which they visit with their flocks, and these rights are seldom disputed. The various tribes wander over definite areas, recognised as their special preserves: but all seek higher districts in the middle of the summer to avoid the heat and pests of the plains, and return to lower level for the winter.

In these migrations they carry with them all their possessions and so they live very simply. A single tent shelters a whole family. During the day time it usually furnishes all the shade to be had, while at night it can be closed to give protection from cold winds.

"It is indeed a fine spectacle to meet a caravan of Kochis moving. Huge shaggy camels lumber down the rocky steeps, followed by donkeys, horses, sheep, goats, and fierce-eyed watch dogs. Among the animals walk the proud Kochis, tall lean, fiery-looking, often carrying rifles on their shoulders. The women, contemptuous of veil, walk stalwartly along with the caravan, some even carrying guns. Young children, lambs, and hens are tied firmly on the top of the luggage.

At night they set up their woven tents, unroll their rugs and set the kettles and cooking pots over their smoky fires. Their only wealth is their livestock. These furnish the staple articles of diet; meat, butter, milk, cheese, curd, and kuroot (dried curded milk). Their wool is spun and woven into cloth for clothing, or is used in making rugs and tents.

This pastoral life, though a difficult one, has many advantages. It is carefree and secure, uniting the advantages of various climates, and affording relief from the monotonous city life in frequent changes of scenes, and never failing-sources of field sports. The nomad, accustomed to hardships, is strong, well built and courageous.

The number of these tent-dwellers has greatly diminished during the past few years, and is still rapidly dwindling. The construction of dams and the creation of new acreage have been undoubtedly, a strong inducement of these wandering tribes to adopt a more settled mode of life."2

1 Shaharani, M. Nazif The Kirghiz and Wakhi of Afghanistan Adaptation to Closed Frontiers and War University of Washington Press, Washington 2002. 274

2 Ali, Mohammed. M.A A new Guide to Afghanistan Kabul 1958. 113, 114, 115